In the past few months my work has been focussed on creating a Docker/Kubernetes based platform that is used by ourselves and our clients to run large scale cloud deployments. The platform, Amdatu RTI, is shaping up nicely, but recently we found something unexpected as Arjan Schaaf blogged about as well. The RTI is cloud provider agnostic and we’re currently running on Azure, AWS and DigitalOcean.

We started running on Azure only recently and have the first deployments up and running. We started to get the feeling the performance of the applications on Azure isn’t great compared to other environments. So we started measuring. I created some Gattling stress tests that similate a user on a sample JavaScript application. The user would request the index.html page, a 200kb minified JavaScript file and some css, all gzipped. Nothing fancy you would say.

The tests quickly showed that performance was far from optimal; avaraging 450ms to download just the 200kb JavaScript file. Not exactly a recipe for sub-second load times…

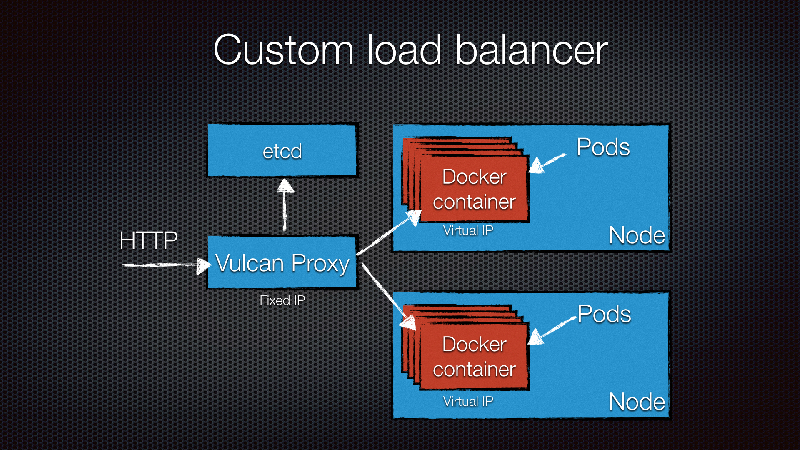

We use New Relic on our servers, so started looking there expecting to find an overloaded CPU, an angry garbage collector or some other sign of busy servers. None. So it must be the Vulcan Proxy that we use for load balancing? Nope.

It turns out the servers, both the Kubernetes nodes as well as the load balancer, were maxing out their network interfaces. Maxing it out at 5mbit/s in and 5mbit/s out that is… My phone’s 4g connection is literally faster than an Azure cloud server!?

Getting the hard numbers

We couldn’t believe what we were seeing, so decided to start testing network speed in isolation. We started some new machines and used qperf to test network performance between two machines. Arjan Schaaf created a Docker container for this that we can simply run on the first machine as:

docker run -dti -p 4000:4000 -p 4001:4001 arjanschaaf/centos-qperf -lp 4000and on the second machine

docker run -ti --rm arjanschaaf/centos-qperf ip-of-server1 -lp 4000 -ip 4001 tcp_bw tcp_lat conf| Instance type | Mb/s | Latency | Price per hour |

|---|---|---|---|

| A0 | 590 KB/sec | 289 us | €0,0135 |

| A1 | 12.5 MB/sec | 281 us | €0,0604 |

| A2 | 24.8 MB/sec | 426 us | €0,1207 |

| A3 | 48 MB/sec | 465 us | €0,2413 |

| A4 | 310 MB/sec | 94.2 us | €1,8246 |

| D1 | 56.3 MB/sec | 276 us | €0,1363 |

| D2 | 117 MB/sec | 178 us | €0,2726 |

Ok, so apparently you get what you pay for from Microsoft… The cheaper instance types are simply unusable.

So is this a practical problem or is this something you would just see under unrealistic load testing? On A2 machines (and slower) it’s definetly a real problem. Even with a single user the response times are horrible (I mentioned the 400ms JavaScript file). Modern web applications often make multiple requests to request static files and RESTful resources. In our simple demo app, which does use minify and compression this added up to multi second page loads, even without external components like databases being involved in the process! Research has shown that slower page loads translate directly to less sales/conversion, so this is very bad.

Running on DigitalOcean

Quite disappointed by Azure, we decided to run similar tests on DigitalOcean and AWS for baselining. Although we didn’t have any raw numbers to back it up, we never had the impression that this was a problem at all on either AWS or DigitalOcean, while we have been running some large scale deployments for several years.

The first possitive surprise came from DigitalOcean. I ran the tests on two $5/month machines.

| Instance type | Mb/s | Latency | Price per hour |

|---|---|---|---|

| $5/month | 108 MB/sec | 157 us | $0.007 |

Wow, well done DigitalOcean! For the price less than the cheapest Azure machine we get network performance comparable to the far more expensive D2 instances. Nothing else to say about this, this is just absolutely great.

What does that mean in practice? Well, it’s comparing apples to oranges (in favor of Azure) but downloading a 400kb compressed JavaScript file averaged at 170ms download time. That’s twice the file size at less than half the response time compared to the Azure A2 example!

Running on AWS

We have a lot more experience running deployments on AWS, and we never had the impression that networking was a bottleneck. Of course our Azure tests made us curious about the numbers.

On AWS the cheap instance types have low/moderate network performance according the documentation. We use t2 instances quite a lot that fall into this category, so we were very curious to see what low/moderate means. More expensive instance types have higher network performance guarantees, on the more expensive instance types you can setup placement groups to force VM placement for optimized networking.

| Instance type | Mb/s | Latency |

|---|---|---|

| t2.micro | 126 MB/sec | 196 us |

| t2.small | 126 MB/sec | 202 us |

| t2.medium | 126 MB/sec | 124 us |

| m4.large | 130 MB/sec | 96.5 us |

| m4.xlarge | 267 MB/sec | 83.5 us |

| m4.2xlarge | 186 MB/sec | 80 us |

| m4.large within placement group | 130 MB/sec | 102 us |

| m4.xlarge within placement group | 267 MB/sec | 87.3 us |

| m4.2xlarge within placement group | 186 MB/sec | 74.5 us |

These are excellent numbers. I can’t really explain why there is no difference between using a placement group or not, but there’s not much to complain about here.

AWS also supports availability zones (separate data centers), so we also tested with servers that run in different zones. As you can see the latency is higher, but the numbers are still excellent.

| Instance type | Mb/s | Latency |

|---|---|---|

| t2.micro | 124 MB/sec | 411 us |

| t2.small | 125 MB/sec | 415 us |

| t2.medium | 124 MB/sec | 414 us |

| m4.large | 130 MB/sec | 360 us |

| m4.xlarge | 267 MB/sec | 333 us |

The numbers on both AWS and DigitalOcean mean that even for the cheaper instance types the network is not a bottleneck. This gives the flexibility to choose machines on what an application needs on CPU and memory resources. The Azure situation forces you to pay for idling CPUs just to get enough bandwidth.

Weave - making things (way) worse

Ok, so raw networking speed at Azure is pretty bad. But it can get worse. In our Kubernetes based clusters we also started using Weave for virtual networking, so that our Docker containers get their own IP addresses. Other services, like our load balancer, can use those addresses.

We found some other posts that indicated that Weave isn’t great for performance. We ran the same tests using Weave, and it’s bad. Really bad.

| Instance type | Mb/s | Latency |

|---|---|---|

| Azure A0 | 590 KB/sec | 419 us |

| Azure A1 | 9.11 MB/sec | 483 us |

| Azure A2 | 10.3 MB/sec | 557 us |

| Azure A3 | 12 MB/sec | 483 us |

| Azure A8 | 51 MB/sec | 188 us |

| Azure D1 | 17 MB/sec | 456 us |

| Azure D2 | 24.6 MB/sec | 446 us |

| DigitalOcean | 9.7 MB/sec | 299 us |

The tests were started the same way as before, only we configured Weave and Weave Proxy so that Docker would attach to Weave. You can see that the faster the underlying network stack, the bigger the performance penalty.

Weave recently announced Weave fast datapath. This hooks into the kernel to provide better performance, while still offering the ease of use of Weave. I only tested this on DigitalOcean, but the results are promising. Not native performance, but acceptable. Hopefully the Weave fast datapath will be released soon.

| Instance type | Mb/s | Latency |

|---|---|---|

| $5/month | 71.3 MB/sec | 196 us |

The Weave folks where very quick to respond to Arjan’s original post about this topic, which includes an answer to “Why would anyone not use Weave fast datapath”.

- It’s been much less battle-tested than weave’s user-space packet forwarding code. The preview release went some way to addressing this.

- It doesn’t traverse firewalls in the preview release. We plan to address this before it makes it into a mainline release of weave.

- It doesn’t support encryption. We’re looking at options for how to support this, but the initial mainline release of fast datapath will be unencrypted only.

If these are show stoppers depend on your situation, but for us the path is clear: Fast datapath FTW.

Flannel

An alternative to Weave is Flannel, which is part of the CoreOS stack. Looking at features it doesn’t really matter much if you use Weave or Flannel. Weave has multicast support, but we can easily live without. Flannel comes with different backends, an udp based implementation (like Weave) and a Vxlan implementation (like Weave fast datapath). The udp is slightly faster than Weave, but still comes with a huge performance penalty. The Vxlan implementation looks a lot better as you can see in the table below, getting close to native performance.

| Instance type | Mb/s | Latency | Compared to native |

|---|---|---|---|

| A2 | 22.8 MB/sec | 269 us | -8% |

| D2 | 95.1 MB/sec | 231 us | -19% |

We decided to switch to Flannel Vxlan for now for our Kubernetes clusters, at least until Weave fast datapath becomes generally available.

Load balancer bandwidth

In front of our Kubernetes nodes we run a Vulcan Proxy on separate machines.

When testing performance on slow machines we noticed something funny. The load balancer machine was maxing out the network constantly, flatlining the traffic graphs. The Kubernetes nodes however, had a steady spike/drop pattern in the graphs. This makes sense, the load balancer was alternating between the two Kubernetes nodes. Therefore, the Kubernetes nodes could have a break, while the load balancer was working to deal with the other nodes. This means that when the load balancer uses it’s maximum bandwidth, having more backend nodes really doesn’t help anymore, because they will not be used at all. Of course, if network is not the bottleneck, you will see very different patterns, but it’s something to be aware of.

Closing words

If anything, we learned that we can’t simply assume decent network performance in the cloud. Different providers give different performance, with Azure performing very badly. Although Azure has a nice feature set, as I have been blogging about before, the very disappointing performance might in fact be a very good reason to not choose Azure. Both AWS and DigitalOcean are excellent choices, with AWS having the preference when it comes to a large feature set, and DigitalOCean when it comes to pricing.

With Weave and Flannel; handle with care. These are very useful additions to a Docker network, but in user-mode very costly. Weave’s fast datapath (when it becomes available) and Flannel’s Vxlan backend should be your defacto choice.